Traumatic Brain Injury

Please peruse Traumatic Brain Injury.com and the Centre for Neuro Skills (CNS) for a wealth of information about TBI, its symptoms and treatment.

Essay on TBI (Wear A Helmet!)

Jim Wampler, PsyD, EdS

As a former denizen of a seemingly gentler era and community, I rode my stingray bicycle on the streets of my quiet southern town without fear of abduction, assault (except by an occasional dog) or concern of head injury. Perhaps my parents could have acquired a bicycle helmet for me somewhere, but I have no recollection of ever seeing one. In fact, as I grew older and had the opportunity to try such sports as snow skiing, helmets were simply not in vogue. It was not until I was a young adult and bought my first mountain bike did I don a helmet. Thinking back on the adrenalin rush of plummeting down a mountain of jutting boulders, loose rocks and gnarly roots, my helmet was often the only thing between me and certain demise. It appears that our construal of recreation has been forever inextricably and fundamentally altered, requiring an adrenalin frenzied intensity that was unthought-of several decades ago. As a result, sports account for nearly 20 percent of all head injuries (second to motor vehicle accidents) with equestrian events, gymnastics, and cheerleading being among the most dangerous.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that between 1.6 and 3.8 million sports-related concussions occur in the United States each year. According to the American Association of Neurobiological Surgeons, approximately 600 cyclists die annually as a result of head injuries while some 85,000 concussed cyclists end up in emergency rooms each year. The National Ski Areas Association reports that TBI is the leading cause of skiing and snowboarding fatalities with an additional 15,000 serious head injuries occurring annually.

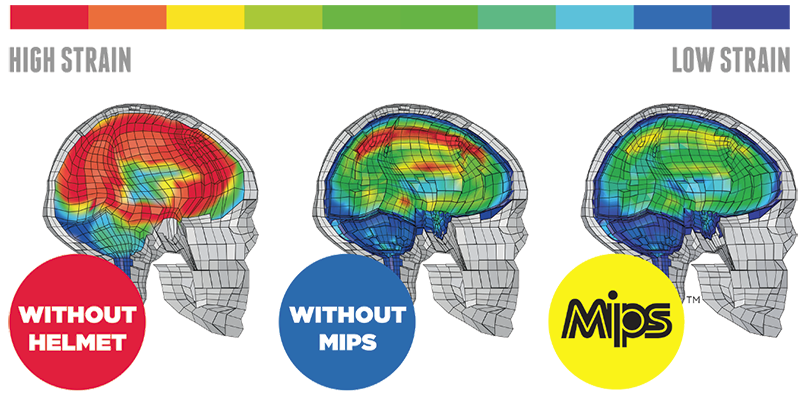

Simply put, our brains were not created to protect and endure the physical forces that we subject them to when participating in most sports (or motor vehicle accidents). Enter the helmet, or as often affectionately referred to as the—brain bucket. Until recently, however, helmet engineering and design had changed very little. The same polystyrene foam in a polycarbonate shell has been in use for the past 20 years. The Consumer Product Safety Commission, in 2006, created a mandatory standard for bike helmets. The regulated testing process, however, leaves much to be desired and most helmets easily pass the mustard. Fortunately, however, helmet makers are starting to spend more on R&D and safer brain buckets are starting to find their way onto the heads of many sports enthusiasts.

When one considers the helmet as a catastrophic insurance policy for your head, it behooves you to purchase a helmet that offers the most comprehensive protection. New polymers such as Koroyd along with innovative technologies like MIPS and HIP-Tec are making inroads in helmet design.

While this short essay has focused primarily on adult TBI and helmet safety, I would be remiss if I didn’t address the astonishing incidence of childhood TBIs that occur each year. One in every 30 newborn children will sustain a TBI before the age of 16. And, half of these incidents will go untreated by a medical professional. A quick perusal of the current literature suggests a strong correlation between moderate to severe TBI with such symptoms as anxiety, ADHD, social difficulties, and behavioral problems.

While the sum of the literature seems to indicate that mild TBI in childhood generally results in little residual impairment, the paucity of current and comprehensive longitudinal research suggests that we may simply be unaware of potential lingering effects. Perhaps unpredicted and tangible deficits emerge at later development periods, yet remain unaccounted for, as all rehabilitation efforts and neuropsychological assistance have long-since ceased. In-any-event, it is apparent that researchers need to engage in continuing research that will further shed light on the impact of mild TBI on childhood development. Hopefully, research and development will continue to pursue better helmets while those in neuroscience and associated professions pursue more proactive means for preventing TBI.

Additional References

Fiarbanks, J.M., Brown, T.M., Cassedy, A., Taylor, H.G., & Yeates, K.O. (2013). Maternal warm responsiveness and negativity following traumatic brain injury in young children. Rehabilitation Psychology, 58, 223-232.

Karver, C.L., Wade, S.L., Cassedy, A., Taylor, H.G., Stancin, T., Yeates, K.W., & Walz, N.C. (2012). Age at injury and long-term behavior problems after traumatic brain injury in young children. Rehabilitation Psychology, 57, 256-265.

Peruzzzi, M. (2013, December). After the crash. Outside, 68-77.

|

BrainVisor – Protect Your BrainBrainVisor does not provide medical or psychological advice, diagnosis or treatment recommendations. The material on this site is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for your doctor or other health care professional's care.

|

|

||

|